GANs have applications beyond Image Editing

A common view about GANs is that they are heavy computationally demanding models with weird and untrackable optimization process that somehow manage to generate realistic images with significantly lower diversity than original data and are mostly useful to make some kind of image editing.

This post will discuss several recent articles (on layout and keypoints prediction, novel view synthesis, creation of synthetic datasets and labels) that challenge the last point of this view.

Why GANs?

Before diving into potential applications, let’s discuss a bit why they rely on GANs.

Basically, for unconditional (or class-conditional, but not image2image) generation in image domain we have the following paradigms:

- Adversarial (StyleGAN2 and BigGAN seem to rock here)

- Gradient estimation or energy-based models (where we iteratively use estimated/discriminator gradients to modify initially random inputs, see Improved Contrastive Divergence)

- Denoising autoencoders or diffusion models (same as above but we replace gradients with “denoising transformation” and modify training accordingly, see DDPM, DDIM or Guided Diffusion papers)

- Autoregressive architectures (like Image-GPT)

- Variational autoencoders (a recent Nvidia take on this is NVAE)

- Normalizing flows (Glow)

- Some mixture of the above (VQ-VAE2, Taming Transformers and lots of other works buried deep on arxiv)

Here I explicitly mentioned methods that currently scale to medium resolutions (like $128 \times 128$) or at least claim to do so (looking at you, VQ-VAE). All of them give somewhat meaningful representations we could play with.

In practical applications, we usually want the model simultaneously close to optimal in terms of quality and diversity, easy to train and to work with, and which samples fast and memory-efficient during evaluation.

According to the recent articles, diffusion models seem to outperform GANs in the first aspect, and so does VQ-VAE2 from DeepMind, but they are spectacularly falling behind in terms of speed.

For instance, as the authors of Deep Diffusion Implicit Models mention:

it takes around 20 hours to sample 50k images of size 32 × 32 from a DDPM, but less than a minute to do so from a GAN on a Nvidia 2080 Ti GPU.

This paper shows that we can make them $20 \times$ faster, but that’s still a far cry of what a powerful GAN gives us. Besides, even if we reduce sampling to just several forward passes, all of those are performed with an autoencoder-like architecture since we need to preserve dimensionality after every step.

The problem may be less profound for VQ-VAE2, but we don’t know for sure. See, neither DeepMind nor “Open” AI have published their checkpoints (thus far) while reproducing their results requires A LOT of compute. So unless you’re satisfied with proof-of-concept work on the Cifar dataset, your only options are to work in those companies or to abandon those models (at least for now).

Other methods are significantly worse than those three in terms of quality. As a result, using some pre-trained GANs currently looks like the best idea.

GANs for feature extraction

To perform unsupervised learning we can extract features of some generative model. This is a very old idea, and dates even back to pre-Imagenet era when Neural Networks were initialized not randomly, but from a weights of Restricted Boltzman Machine. Since then people tried to mix it with basically any paradigm we’ve listed previously, and GANs are no exception. For instance, authors of BigBiGAN proposed to train (guess what) BigGAN model jointly with an encoder, and learn discriminator to distinguish joint distributions of image-latent pairs, where latents for reals are given by encoder (see fig. 1 in their article).

But in practice all those approaches significantly underperform the alternatives, especially with the recent rise of self-supervised learning. Why?

The authors of “Generative Hierarchical Features from Synthesizing Images” (namely Xu Yinghao, Shen Yujun and others) give a somewhat obvious answer - because we evaluate them mostly on problems that are “too discriminative” (I’ll elaborate on that later).

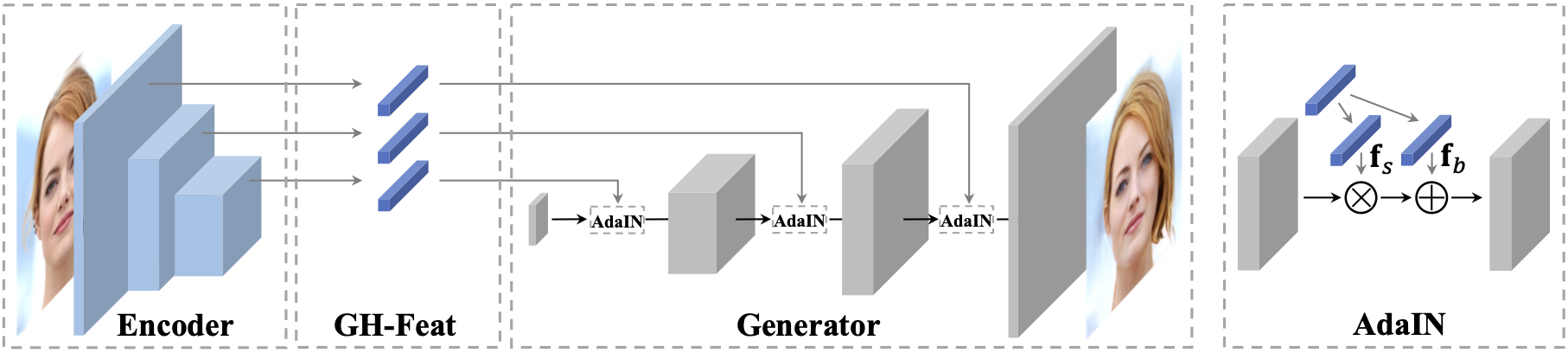

Namely, they take an existing pre-trained StyleGAN model and train a separate resnet-like encoder to predict its adaptive Instance-Norm statistics:

This scheme relies heavily on the fact how StyleGAN works - it samples random latent $z$, passes it through a deep fully-connected “mapping” network to get the feature vector $w$, then uses it at every layer of “synthesis” network (which receives a constant input) to perform an adaptive version of instance normalization. The statistics for such normalization are linear projections of $w$, and they are precisely what encoder tries to predict.

So in essence, the authors freeze the generator, replace the mapping part with encoder, and train the whole system on real images as a large adversarial autoencoder (using L2 and VGG perceptual distances, as well as a separate discriminator).

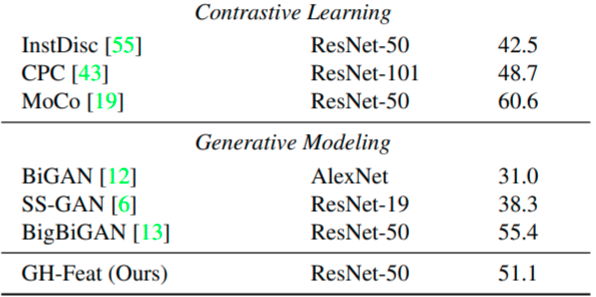

Then they evaluate encoder features. For Imagenet classification, it performs quite bad - the table below shows top-1 accuracy of linear model trained on the features:

Note that current Self-supervised SOTA SwAV reaches even higher accuracy of $75.3\%$ with the same ResNet-50 architecture, so the gap is actually twice bigger.

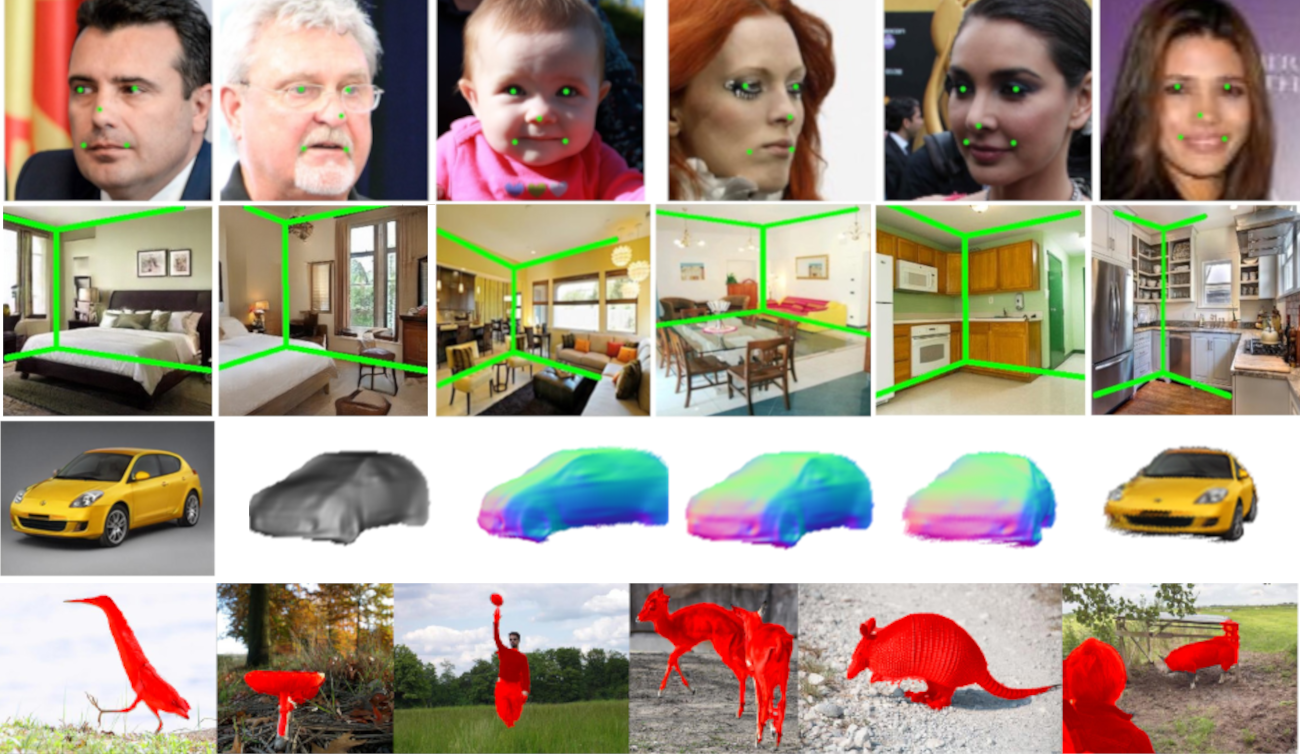

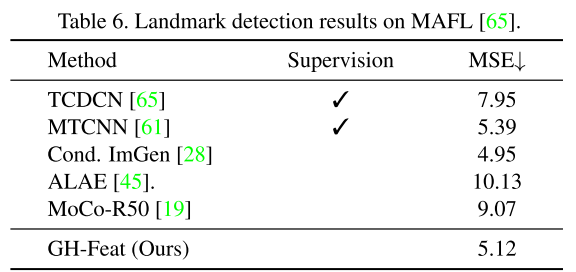

However, things change when we switch to keypoints prediction task:

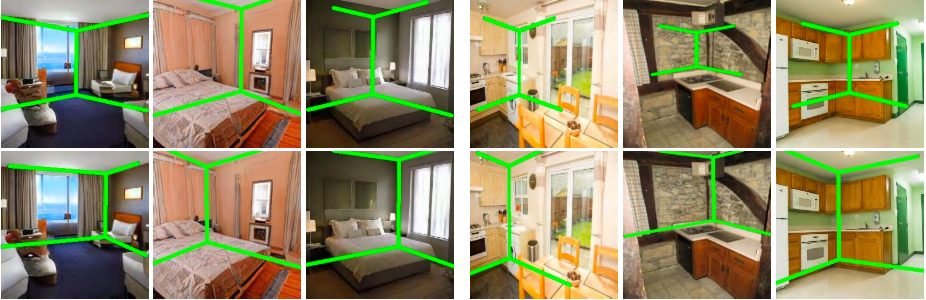

Or the problem of layout prediction (when we need to outline basic separation lines betwen walls, floor and ceiling):

Here the top and bottom rows correspond to the predictions made by MoCo and GHFeat respectively with roughly similar encoder architectures.

Let me drop some intuitive pseudo-scientific explanation about this. To generate diverse and realistically-looking images the AdaIN statistics $y_s$ should contain as much information about the output as possible. Those will include many finest details like the texture of grass in outdoor images or the exact position of different objects in scene. In contrast, the features extracted from discriminative models (including those trained with Self-Supervision) are expected to have only features that correlate well with the class or instance labels and thus drop unrelated information about the image. Since the representation capacity of any model is limited, we’re either left with a model that highly specialized for more abstract problems but fails on some low-level tasks or a model that could be used in a variety of low-level tasks but has less useful features to solve abstract problems.

Overall, the takeway is - if you need to solve a given downstream task, a network with better classification accuracy does not necessarily perform better on it. In cases when classical augmentations (like color jittering or random cropping) could make it harder to solve, it might be reasonable to replace your favorite Self-supervised feature extractor with GHFeat.

Image rendering with GANs

As the previous case sounded quite obvious, here is something that does not - we could use GANs to get 3D object shape from a single image.

To get an intuition of how this works, let us firstly consider the problem of 3D estimation from a multi-view data. That’s it -

Synthetic datasets and labels

WIP, stay tuned